The Obligation of Self Sacrifice -An Introduction to the Methodology of Rabbi Chaim of Brisk

The Obligation of Self Sacrifice -An Introduction to the Methodology of Rabbi Chaim of Brisk

The Obligation of Self Sacrifice -An Introduction to the Methodology of Rabbi Chaim of Brisk

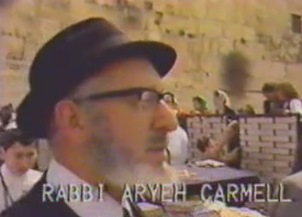

By Rav Aryeh Carmell O.B.M.

INTRODUCTION

The Torah embraces all of life and provides for the most varied eventualities. The Jew who follows the Torah holds his life continually at G-d’s disposal. It is not surprising, therefore, to find the Halacha dealing with the Mitzva of martyrdom and the conditions governing this, in the same matter-of-fact vein in which it deals with the Mitzvot of tefillin or matza.

The Halacha tells us that there are three cardinal sins for which one must sacrifice one’s life rather than committing them. This article will explain what these are and will go on to discuss the rationale of this Halacha. At the same time, it will give a typical example of the methodology of Rabbi Chaim Soloveytchyk of Brisk (Brest-Litovsk), the

twentieth-century Halachic genius whose revolutionary analytical method has been adopted in practically all yeshivot in our time.

After briefly setting out the Talmudic sources, we shall introduce a dispute between the poskim (Halachic decisors) on an important aspect of this subject. We shall then see how Rabbi Chaim applies his analytical technique to the key concept so as to illuminate both sides to the dispute. The article will conclude with a brief practical note.

SOURCES

The Talmud 1 states that all the prohibitions in the Torah are set aside to save life, except three: idolatry, adultery 1a and murder. For idolatry, the Biblical source is the verse in the Shema: ‘And you shall love G-d, your G-d, with all your heart and with all your life…’2, i.e., one shall not abandon one’s love of G-d, even at the cost of one’s life.

Adultery is included because it is compared to murder 3; What of murder itself? The Talmud says that this needs no Biblical support. It stands to reason, and the case is cited of a Jew who came to Rava 4 for guidance. The local ruler (a non-Jew) had ordered him to kill a certain Jew on pain of death if he failed to do so. What should he do? Rava did

not hesitate. ‘Let them kill you, but do not kill, ’he ruled. ‘Who says your blood is redder, perhaps the other fellow’s blood is redder than yours?’

The homely proverb masks a profound insight. The people of the Torah must look at things from G-d’s point of view. The only reason why G-d provided that His commandments might be set aside for the sake of saving life is because life is precious in His eyes. But here a life will be lost either way. There are no means of determining which life is more precious to Him. Therefore there are no grounds for setting aside the prohibition of murder. Therefore,

one must let oneself be killed rather than kill.5 (This assumes of course that there is no other way out of the dilemma; either by escape or by killing the bully or otherwise.)

LATER DEVELOPMENT

The question is raised whether the obligation to sacrifice one’s life rather than commit adultery applies equally to men and women. The opinion is expressed in Tosefot 6, that women are not included because the woman’s role is merely a passive one. She is being forced to submit to an act, not to commit one. After all, says Tosefot, the case of adultery is derived from the case of murder 7; and if one were ordered to be a completely passive participant in an act of murder (e.g. to allow oneself to be thrown forcibly against a baby so as to crush it) would one have to resist at the cost of one’s life? Certainly not, says Tosefot; it is the thrower who is committing the murder, not oneself. The

principle ‘Be killed but do not kill’ applies only where one is ordered to commit a positive act. Where no criminal act on one’s part is involved, one’s first duty is to preserve one’s own life.

Here the converse is true: Who says that his blood is redder than mine? Similarly, then, in the case of enforced adultery, since the woman’s role is completely passive she is not obliged to resist at the cost of her life. Thus Tosefot. But Rambam (Maimonides), in his Code 8, does not introduce this distinction, and it is therefore apparent that in his opinion there is no difference in this respect between man and woman. But how does Rambam deal with Tosefot’s arguments?

CONCEPT-ANALYSIS OF RABBI CHAIM OF BRISK

To illuminate this dispute, Rabbi Chaim subjects the concept of ‘Who says your blood is redder than his?’ to extremely subtle analysis 8a. The concept is, as we have seen, that of the equal value of the two lives concerned, i.e. the other person’s life and your own life. The resulting deduction, says Rabbi Chaim, may take two alternative

forms:

(1) The two lives (one’s own and the other man’s) are equivalent. Therefore one may take no action to end his life in order to save one’s own. (This follows the general principle that when faced with two opposing but equal factors, the correct course is to take no action.)

(2) The two lives (one’s own and the other man’s) are equivalent. Therefore the prohibition of murder cannot be set aside in order to save one’s life.

At first sight, these two statements seem completely indistinguishable. But this is a typical characteristic of Rabbi Chaim’s analytical method. On further scrutiny, these two alternative statements will be found to contain the seeds of the solution. Let us look at them again, and see if we can expand them slightly.

(1) ‘You may take no action to end his life’—No action; but if one can save one’s own life by passive participation, this would be permissible. And this would be the case even if such passive participation were to be deemed a form or murder. It is only active murder that the principle precludes; murder by non-resistance (if there were such a thing) is not precluded.

(2) ‘The prohibition of murder cannot be set aside’— The normal right and duty of saving one’s own life does not apply where murder is involved. Any form of murder. If passive participation were to be considered a form or murder, then it too would be prohibited.

In practice, all agree that allowing oneself to be used as a tool for someone else’s murderous act does not count as murder on one’s part. The practical difference emerges, however, when we consider the case of enforced adultery. The woman’s role is a passive one, yet there is no doubt that she is participating, however unwillingly, in an act of adultery.

In the normal case of the crime, where both are consenting parties, it is certainly true that both woman and man are considered as having committed adultery, even though the woman’s role may have been passive 9, and there is no essential distinction in this respect when consent is lacking.

Now since, as we have seen, the law as regards adultery is derived from the law as regards murder, we can substitute adultery for murder in each of the two statements above, and see what results we get.

(1) Adultery must be avoided at all costs. Therefore, one may take no action to commit adultery in order to save

one’s life.

(2) Adultery must be avoided at all costs. Therefore the prohibition of adultery cannot be set aside even for saving life.

Now if we draw the necessary conclusions we shall see how the two sides in the halachic dispute on the women’s obligation depend on which of the two formulations we adopt.

(1) ‘You may take no action.’ But the woman’s role in adultery is passive. No action is demanded of her. Therefore she would not be required to sacrifice her life in resisting. —This corresponds to the position of Tosefot.

(2) ‘The prohibition cannot be set aside.’ But the prohibition as such applies equally to men and women, irrespective of their roles. Therefore the woman too would be required to resist to the death—this corresponds to the position of Rambam.

By this very elegant piece of analysis, Rabbi Chaim has demonstrated how the proponents derive their views from differing formulations of the basic concept.

SUPPORT FOR ONE VIEW FROM A DIFFERENT TALMUDIC PASSAGE

But Rabbi Chaim is not quite finished yet. Is it possible to derive support for either of these formulations from any other Talmudic source? Rabbi Chaim thinks it is.

There is a famous discussion in the Talmud 10 on the classic case of the two men in the desert, one having a flask of water and the other having none. The water is just sufficient to enable one of them to get to civilization, but not both.

If one drinks, he will live and the other will die. If both drink, both will die. Ben Peturi 11 taught: Let them both die rather than that one should see the death of the other. But he was later overruled by Rabbi Akiva who taught that one’s primary duty is to preserve one’s own life, deriving this from a verse in Leviticus 12.

Now, says Rabbi Chaim, this is a clear support for the second of our two formulations. Let us turn back for a moment to our discussion of the case of murder. If it were only active murder that the principle precludes, there could have been no basis for Ben Peturi’s teaching at all and Rabbi Akiva would not have had to adduce a verse in Leviticus to refute it. For there is no hint of active murder here: by drinking the water from his own flask the first man is making only a very negative and indirect contribution to the death of the other. If, however, a passive contribution to someone else’s death may also be within the ambit of our principle, we can understand Ben Peturi’s assumption. All he did was to assume that such anegative contribution was also to be deemed a form of murder, and as such, of course, not to be undertaken even to save one’s own life. But it was left to Rabbi Akiva to demonstrate that such a negative act cannot he equated with murder in any sense: it is merely a question of which life to save; and the Torah tells us that, in such a case, our first duty is towards the life that G-d has given us.

Rabbi Chaim considers that this provides support for Rambam’s point of view as set out above.

PRACTICAL NOTE

Unfortunately, the violent history of our times has shown that these laws are as relevant today as when they were first promulgated thousands of years ago. As regards the decision in practice, it is generally accepted (in spite of Rabbi Chaim) that the view of Tosefot prevails and a woman need not resist to the death if threatened with enforced adultery 13. This applies, however, only to the case where the threat is applied solely for the threatener’s own private purposes. Where anti-Jewish or anti-Torah persecution is involved, all category-differences disappear and all Jews are obliged to resist all such persecution to the death. This was done for example in 1943 by the forty-three Beth Yaakov girls who accepted martyrdom rather than fall alive into the hands of the Nazis, following a long tradition of such acts of heroism.

When we come to the equally agonizing questions of weighing life against life, the principle enunciated by Rabbi Akiva shows us how misleading our own human concepts can be. Instead of a crude conflict between the self and the other, he shows us a choice between two G-d-given lives, both entrusted to our care.

The Halacha, as always, weighs up the opposing factors and tells us what the justice of the Torah requires. Rabbi Akiva’s principle is certainly taken as the norm, but it is open to the individual to make his own judgment and sacrifice his life if, by so doing, he can save his comrades or one who is greater than he in Torah. This is attested to by a long line of heroes, from the ‘martyrs of Lydda’ 14 down to our own times.

________________________________

REFERENCES

1. Sanhedrin74a.

I a. Strictly speaking the term gillui arayot includes all those forbidden unions which the Torah makes punishable by death or karet—see Leviticus ch.20.

2. Deuteronomy 6: 5. The words usually translated ‘with all your soul’ should properly be rendered ‘with all your life’.

3. Ibid. 22: 26, where the Torah compares the rape of a wedded maiden to an act of murder.

4. A leading Amora (Talmudic sage) of Fourth-Century Babylonia.

5. This reasoning is set out in Rashi’s commentary ad loc.

6. Commentaries on the Talmud originating in the Yeshivot of Twelfth-Century France. Tosefot means ‘Addenda’ and is in the plural; but it is customary to refer to them in the singular (‘Tosefot says’); this is an abbreviation for ‘the author quoted in Tosefot says’.

7. See note 3.

8. Hilchot Yesodei HaTorah65:1.

9. Deuteronomy 22-22.

10. Bava Metzia62b.

11. A Mishnaic sage of the First Century.

12. Lev. 25:36 ‘Your brother’s life is with you’— implying that your life has precedence.

13. Shulchan Aruch, Yoreh Deah, 157:1 (gloss).

14. Taanit18b and Bava Batra10b (Rashi). The martyrs of Lydda (or according toone version, Laodicea) were two brothers named Lulianus and Papus who lived in the time of the Emperor Trajan. This was an ancient example of ‘blood libel’, when a decree of destruction was issued against the Jews because a princess had been found murdered. It was averted by the brothers falsely admitting to the crime and taking the punishment upon themselves. In earlier times a day in the Jewish calendar was set aside to commemorate their heroism. On the moral duty of self-sacrifice, see Rabbi N. Z. Y. Berlin: Haamek She’elahon She’eltotof Rabbi Achai Gaon, P. Shelach, 129:4.