“G-d said to Abraham ‘Get yourself from this country, from your relatives, and from your father’s house to the land that I will show you’”.

The first verse of this week’s Sedra is fascinating. The Torah tells us that Abraham was no youngster when he was told to leave his homeland – he was 75. Think for a minute – imagine a relative of yours who is, let’s say, of advanced years.

Could you imagine him packing his bags and leaving his family at the drop of a hat, not even knowing his destination? Surely not even the most youthful grandfathers would contemplate taking off on an Interail holiday without so much as a return ticket.

Not so with our forefather Abraham. For he received his orders directly from G-d, whom he trusted implicitly. He didn’t ask why. He didn’t ask where. He just did it.

We can learn a great lesson from this. Sometimes (let’s not kid ourselves – many times!) we are commanded in the Torah to do something which we feel is illogical, which we don’t understand, or which we just don’t agree with. How many of us um and ah, laugh and joke, or even violently disagree. But how many of us just get up and do it?

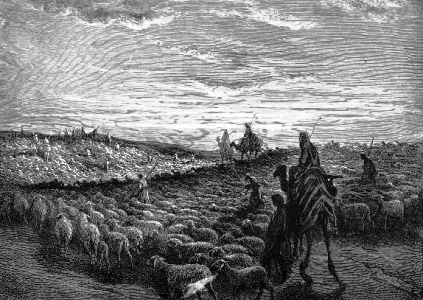

Nevertheless, we must bear an important lesson in mind, which we learn time and time again in Sefer Bereishit: “Ma’aseh avot siman lebanim” (the events of the fathers are repeated in the lifetime of the children). That is to say, what happened to them back there more often than not happens to us. History does repeat itself. The Jewish people have spent little time ‘at home’; for most of their history they have undergone Abraham’s first trial, wandering from nation to nation, from one country to another. Exiled from their homeland. It’s one long travelogue.

How do we stop it? How can we all settle down in the Holy Land without any trouble? How do we stop the persecution? Simple – we should cry for Mashiach.

“But how can I believe in the Messiah? Isn’t that a fairy story?”

“Who am I to believe in these things? I want reality.”

“I’m not one of those Lubavitch people. I don’t need to spent time asking for Mashiach.”

But why don’t we just do it?

That’s not the only example of ma’aseh avot siman lebanim. Further on, we are told that when Abraham reached the Land, he found the Canaanites were living there. He didn’t find the Promised Land uninhabited, ready to receive him. Moreover, there was a famine in the Land, and Abraham was forced to leave. Often someone makes plans to make aliyah and live in Israel, but finds no work – “There was a famine in the Land.” Sometimes he is forced to leave Israel for a while – “and Abram descended to Egypt.” And sometimes we will have to fork out for a cave to live in and a stony field, like our father Abraham, who paid four hundred shekels for the Cave of Machpelah. It isn’t always easy in the Land of Milk and Honey. However, despite all odds, Abraham still soldiers on. He never questions G-d. He just does.

But we are told another thing. The famine in Canaan was not so severe. There were people who remained there without starving to death. Didn’t he have money and resources with him from where he left? Surely Abraham did not leave Canaan because he wanted superior food…

Of course not. The Gemara tells us that in Abraham’s old age, he sat at the head of a yeshiva, where people were taught about G-d and the perfection of human character (Yoma 28b). Most likely he supported this yeshiva with his own funds (who else in that generation would have supported it?). Moreover, to win souls in this worldwide outreach program that he had going on, Abraham would offer the passing travellers free food and drink, and so bring them under the wings of the Divine Presence.

That’s all fine and dandy – when you have the money.

When the famine became severe, Abraham used up all his wealth to support the yeshiva, which was his mission in life. To keep it functioning he was forced to go down to Egypt with Sarah, endangering them both. They willingly put their life on the line for the sake of Torah.

How many of us can say that we do that?

Further on in the Sedra we read about the battle between the four kings and the five kings, which was the first world war. In this section we find a very interesting verse:

“Then there came the fugitive and told Abram the Hebrew, who dwelt in the plains of Mamre the Amorite, the brother of Eshcol and Aner, these being Abram’s allies.”

Five questions can be asked about this verse:

1. It says that the fugitive ‘told Abram’, but it doesn’t say what.

2. Why mention that Abraham lived in the plains of Mamre when that has already been mentioned a few verses earlier?

3. Why mention here that Mamre, Eshcol and Aner are his allies?

4. It says further on “Abraham heard that his kinsman was taken captive”. From whom did he hear this? If it was from the fugitive, why not mention it here?

5. Who is this fugitive anyway?

It seems the fugitive (we will talk more about him later) like anyone fleeing for his life, was half-dead with terror and exertion. He barely blurted out that Lot (Abraham’s nephew – the ‘kinsman’) was in trouble, but not much else. Normally, when a person is told that a relative is in danger, he does not immediately rush out to save him unless he has a clear account of what happened. Abraham, the supremely pious, did not behave in this way. Even though he was living in Mamre, far from the war, and even though he had his three military allies Mamre, Eshcol and Aner, he still tried to prise the story from the mortified fugitive. He eventually pieced together that his nephew had been captured in the war, and he went to rescue him.

And now to reveal the identity of the mysterious fugitive… it was none other than Og the giant, who Chazal tell us escaped from the flood many years earlier by hanging on to the ark. Rashi tells us that Og’s intention in telling Abraham about his captured nephew was for Abraham to recklessly rush into the battle zone, thereby getting himself killed, leaving Og to marry Abraham’s wife, Sarah. This was not the noblest of giants. But funnily enough, G-d rewarded Og for informing Abraham. We find an explanation for this in the gemara (Gittin 68) “One who pleases a totally righteous man merits eternity”. Despite his wicked plans, Og gave Abraham contentment – Abraham ended up killing the four kings and rescuing Lot, thereby sanctifying G-d’s name. Indeed, G-d rewarded Og with long life – he lived until the time of Moshe.

After Abraham’s tremendous victory, the nations of the world called him a god. Think for a moment about Abraham’s previous track record: choosing a fiery furnace rather than bowing down to King Nimrod, travelling across the land praising G-d’s name, providing hospitality to every passer-by, performing incredible acts of justice and charity. None of this inspired the adulation of the masses. But once he was a war hero, he was a ‘god’.

Such is the mentality of the gentiles. Whereas the Jews honour great Torah scholars and men of piety, the nations honour a man through his ‘hands of Esau’. We see this even in modern times: the United Nations didn’t recognise the Jews as a nation worthy of independence until they had given seven Arab nations a sound beating after being attacked.

SHABBAT SHALOM